If I am to truly tell you about our trip down the Amazon into a real Amazonian village, I need to start by writing about the river. Everything here is dependent on the river. Food comes from it in a dizzying variety. It provides the conduit between villages. The river is as much a part of life here as air.

If I am to truly tell you about our trip down the Amazon into a real Amazonian village, I need to start by writing about the river. Everything here is dependent on the river. Food comes from it in a dizzying variety. It provides the conduit between villages. The river is as much a part of life here as air.We were loaded onto canoes, feeling large and ungainly. Actually, in comparison to Eni, who traversed the outer rim of the canoe, I felt like a bull elephant trying to place a china cup onto a shelf, graceless and oh-so-foreign to this enchanted place. I felt every inch a son of the concrete city, a stark contrast to the people of this place. They move with grace. They move with confidence through a land I could never have dreamed up in my wildest moments.

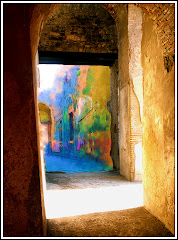

The canoe glides down the river.

The only sound is the soft puttering of the engine. We are all silent. No conversation is possible. Our hearts are drinking it all in: the gathering darkness, the sweet scent rising from the water – the dynamic footprints of life swirling around us like delightful spirits.

I read that paragraph – and think that if I were you, I would snarl “who is this guy? Doesn’t he know when to quit?”

But if I am going to do my job – to truly convey to you the atmosphere of this place I need to use words like “life” and “dizzying” and even “enchantment.” There is nothing in your life experience that can possibly prepare you for the Amazon. Nothing. It defies words and every metaphor I create seems pale and thin in the face of that indescribable something that is the Amazon.

As I write this, I am listening to Etta James sing the songs of Billie Holiday. The music is perfect – the harmony is also perfect and resounds with a lazy passion. It is a perfect complement to the things I am attempting to remember and tell you about. Being in the Amazon is like listening to Etta sing. It is like surrendering yourself to good music, laying back in a comfortable place and letting your spirit dance with the music. You either get that or you don’t.

Okay – enough flowery crap.

We travel down the river for too short a time. We see huts with only the roofs above the water.

“When the river recedes,” says Eni, “These will be used again. For now they wait,” he says with a shrug. The shrug is eloquent. It’s an acceptance of the Amazon and what it does to their lives.

Eventually we come to a landing. It is a landing only in the most generous terms. There is a rough outcrop of wood. We beach the canoes on the land. Caramel skinned people stop and smile and wave and then go about their business. We have arrived in a village. This is not a tourist place. It’s an Amazon village.

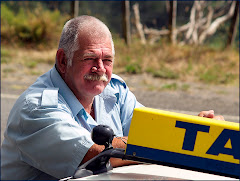

Most of the people who live here work in the jungle hotel we have just left. Eni tells us that they were approached by the businesspeople who own the land to build the hotel…and then work in it after the building was done.

Eni is trying to herd the tourists into an open walled shed where a woman is using a large wooden spoon to push a light brown crumbly substance around in a four foot wide pan. Her name is Mary and she is the head of the village.

She nods and smiles as we enter. Then she looks away. It’s not deference. It’s not shyness. It is again a flash of that unique something about the people here. It is just their way, I suppose. Eni invites us to reach into the pan and taste some of the crumbly stuff. All eyes turn to Mary. It is us being non-Amazonians. We are looking for permission. She nods. As she smiles, I notice she is missing some teeth. She’s not an old woman.

The flour tastes like it looks: brown and dry and crunchy like peanut shells under my teeth.

I start moving around the area. There’s an orderly disorder here: items tossed to one side in a manner that sort of makes sense: disparate glass items in a box, tools tossed carelessly into one corner.

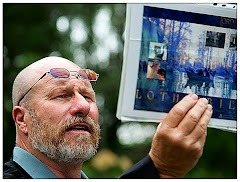

I notice we are being followed by two little boys who hang shyly on the fringe of the crunchy flour tasting tourists. I smile and they smile back. I raise the camera and my eyebrows. They cover their mouths and giggle.

I ask Mary if it’s okay to take their picture. She smiles. She shrugs and then nods.

After the images are done, I ask her if I can give the boys a dollar. This time she pauses and I have the very strong sense I have said something wrong. Then she nods and I give the boys some money, even as I wonder if I have offended our host. It’s not like I am worried about getting a curare dart in the neck. I’m not. But I am constantly getting the impression that the people here often never give voice to what’s really going on inside them.

I hear laughter, children’s laughter, and I cross the compound. A volleyball net has been tied to two trees and there are eight children playing a spirited game. Others hang on the fringes watching and laughing. This time I don’t have the sense this is being put on for the visitors. This is just people living their lives and we can choose to join in or not.

Sheree has found a place to shop, incredible as this sounds. Mary has laid out some t-shirts (all made in China) and Sheree is looking at them carefully. I know her interest isn’t so much in the shirts as it is in the interaction and besides all that, you have to admit that buying t-shirts in the Amazon jungle is pretty cool. So is supporting the people who have opened their homes to our visit.

Sheree has found a place to shop, incredible as this sounds. Mary has laid out some t-shirts (all made in China) and Sheree is looking at them carefully. I know her interest isn’t so much in the shirts as it is in the interaction and besides all that, you have to admit that buying t-shirts in the Amazon jungle is pretty cool. So is supporting the people who have opened their homes to our visit.

She selects three and pays with one of our three Brazillian bills.

We pile our ungainly selves back into the canoe and wave goodbye. The villagers look up from their volleyball game and wave back. Then life continues as it has for hundreds of years. We float away on our path – and they continue on theirs. I am thinking, as we putter back to the Amazon Hotel for a very welcome feast, that it is pretty cool that our lives intersected for this brief moment and then parted again.

Later on that night I will hold an Amazon alligator in my hands. But that’s another story.